PLASTIC

MARS Gallery (VIC) Oct 2021

Plastic

catalogue essay by Briony Downes

Melbourne-based artist Penelope Davis creates sculptures from silicone, a highly versatile material that lends itself to an infinite number of uses. Easy to work with and resistant to extreme temperatures, silicone is the go-to material for prosthetic limbs, cookware, phones and building construction. As a sealant, it coats the surfaces of our homes, highways and electronics. In short, silicone is everywhere.

While silicone is undoubtedly a useful material, with such widespread proliferation comes a flip side. Its structural resilience means silicone is not easily broken down and this stubborn longevity inevitably outstrips its initial period of usefulness. Over time, silicone ends up like plastic, becoming a major component in global waste and greatly adding to the environmental degradation associated with mass production and the over consumption of single use objects.

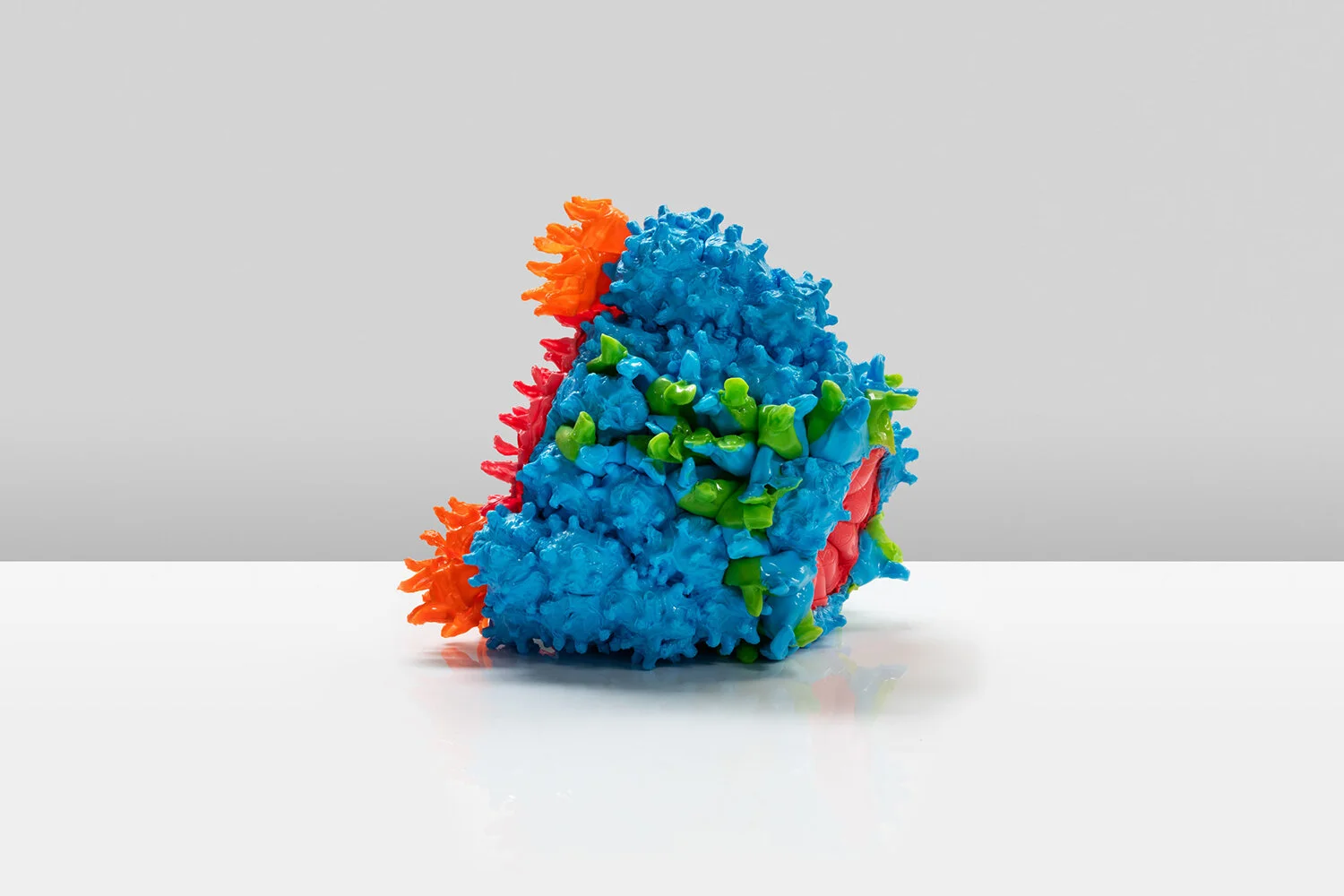

In Plastic, Davis explores this duality, accentuating the appealing elements of silicone while laying bare the environmental insidiousness of plastic. Comprised of sculptural forms made from multiple components, Plastic initially appears to be a collection of brightly coloured organic specimens, insects or strange marine animals. Upon closer inspection, it becomes apparent the facade of Davis’s sculpture possesses distinctly artificial elements. The innards of hardy structures like Oculus and Pincer bubble and multiply with bulbous protrusions, probing tongues and claw-like pincers. While the hybrid silicone forms seen in Davis’s 2017 exhibition Sea-change were recognisable as jellyfish, the technicolour constructions of Plastic are not as easily pinned down in the real world. They could be wreaths of mutant plant species, radioactive cell clusters or contagious viral pathogens.

While other sculptors working with silicone like Canadian artist Amy Brener, embed everyday objects directly into silicone, Davis instead uses silicone to cast moulds from small plastic objects. These moulds originate from found objects plucked from curb-side hard rubbish piles or unusual plastic paraphernalia purchased at bargain stores. Bottle tops, mobile phone chargers, hamster tunnels and water bottles – the general detritus of everyday life – are the building blocks of Davis’s creations. Once cast in silicone, Davis peels the moulds from their host objects and sews the moulds together, slowly crafting an object into its final form. In direct opposition to the fast paced, fully automated production lines most mass-produced items go through, Davis’s creative process remains slow and without a clear plan. Each creative step builds on the next until an object evolves into being.

The sculptural forms in Plastic represent the fruits of multiple pandemic related lockdowns in Victoria. When COVID-19 hit Australia in early 2020, Davis moved her studio to her home where she worked through each lockdown with her family, each of them toiling away at their respective work and school related tasks. Despite the safety of remaining at home, as Davis worked in isolation she witnessed visual references to COVID-19 unconsciously manifesting in the forms she was making. As each work took shape, some began to resemble spikey conglomerations of virus cells like giant parasitic mutations of COVID-19.

Davis admits working on these pieces during a pandemic had its advantages. She speaks of the ease of working with silicone for pieces like Horn, with the material’s durable elasticity avoiding any risk of tearing and allowing for uncomplicated layering. The soft, fleshiness of silicone was always deliciously spongy and there was a meditative quality in sewing each piece together, a playfulness to the vibrant pigments she used to dye the otherwise clear material. Similar to the anthropomorphic, multi-faceted resin vessels made by fellow Melbourne artist Kate Rohde, Davis’s use of hyper bright colours attracts the eye with colour combinations synonymous with the tiny Poison Dart Frogs of the Amazon forests. Incredibly beautiful to look at but a clear visual warning of danger.

As Davis writes in the artist statement for Plastic, her current work reflects our symbiotic relationship with the natural world and the havoc and loss we are wreaking upon it. She describes her work as both monstrous and beautiful, vigorous yet emblematic of loss. The work speaks to loss of ecosystems, native species and wilderness. This unnerving duality of visual elements connects to the broader environmental implications of Plastic. Secured onto metal armatures derived from upturned wire planters, the tiny pieces contained in works like Bloom and Sprout are constructed in a similar way to the Great Pacific Garbage Patches – hulking mounds of plastic debris collected by ocean currents and held together by tangled fishing nets and discarded ropes. In these calm pockets of the Pacific Ocean, remnants of the relentless global cycle of production and consumption quietly gather and grow larger by the day.

From a historical point of view, Plastic brings to mind the decorative excesses of 1700s Rococo interiors. Embellishing every surface from ceiling to floor with gaudy decoration, Rococo design blossomed voraciously into upper-class interiors throughout France, Italy and central Europe. Characterised by an abundance of natural forms, particularly seashells, vines and flowers, Rococo added a sense of luxury and fantasy to otherwise mundane interiors. Assembled as though destined for a Rococo interior, Davis’s botanically inspired Spout and Snoot possess proboscis-like casts of watering can spouts and long tendrils of silicone dripping like honey. Additionally, a favoured architectural folly in Rococo was the grotto, with the most lavish equipped with theatres, lights and artificial lakes. A direct reference to the fake crystalline growths often found in these man-made caves, Davis’s black and pink structure, Grotto, sprouts spikes that appear as though they have violently sprung from the gallery wall.

Evolving from a background in photography, Davis’s current work stems from a long-term interest in capturing the object in both a visual and physical way. Completing her fine art studies at the Victorian College of the Arts, Davis initially spent time experimenting with photograms – a camera-less process of placing an object onto photographic paper and exposing it to light to create an effect similar to an x-ray. The camera itself became a frequent subject in her photograms, as well as stacks of books. Davis would take these objects into the darkroom and experiment with coloured gels – similar in hue to the colours now dominating Plastic. It wasn’t long before she turned her attention solely to the objects, casting them in silicone and pigmented resin. As a result, Davis eventually dispensed with photography as her main medium and expanded her practice to fully embrace sculpture, creating objects that have since morphed into the meticulously appealing forms of Plastic.

Briony Downes

2021